Information complexity

Information theory is a vastly successful theory underpinning much of our communication technology. In many important communication scenarios it allows one to calculate the precise amount of resources needed to perform a cetrain task. For example, the number of bits Alice needs to communicate to send a string $x_1 x_2 \ldots x_n$ of $n$ random trits (elements from $\lbrace 1,2,3\rbrace$) to Bob is given by $(\log_2 3) \cdot n \pm o(n)$. The number of bits Alice needs to communicate to send $n$ random trits to Bob if Bob already knows half of the $x$’s (regarless of whether Alice knows which locations are known to Bob) is $\frac{\log_2 3}{2}\cdot n \pm o(n)$ etc. These quantities can be written as expressions in terms of things like Shannon’s entorpy, mutual information, and conditional mutual information.

Notions of entropy and mutual information allow to precisely (and losslessly!) describe the flow of information in a variety of settings. They also allow one to write “common sense” statements about information in precise mathematical terms which can then be manipulated. This turns out to be extremely useful in reasoning about communication. For example entropy $H(M)$ represents the amount of uncertainty in a message $M$. Mutual information $I(M;X)$ represents the amount of information the message $M$ reveals about a piece of data $X$. Conditional mutual information $I(M; X|Y)$ represents the amount of information a message $M$ reveals about $X$ to someone who already knows a piece of data $Y$.

The chain rule $$ I(M_1 M_2; X) = I(M_1; X) + I(M_2; X|M_1) $$ is just a precise way to formalize the intuitive fact that what one learned from two messages $M_1 M_2$ about $X$ can be decomposed into what one learned from the first message plus what one learned from the second message when we already knew the first one. The data processing inequality $$ I(X;F(Y)) \le I(X;Y) $$ formalizes the intuition that a function computed on $Y$ cannot reveal more about $X$ than $Y$ itself.

The goal of information complexity is to learn to apply information-theoretic formalism to computational settings. As of now (2021), these tend to work beautifully in models of computation that are simple enough to not support information-theoretically secure computation. Understanding why exactly this happens is an interesting direction for future work. Below we give some examples of results based on information complexity from the 2010-2020 period. In some cases the results are new, while in others they give conceptually simpler proofs or more general statements of existing theorems.

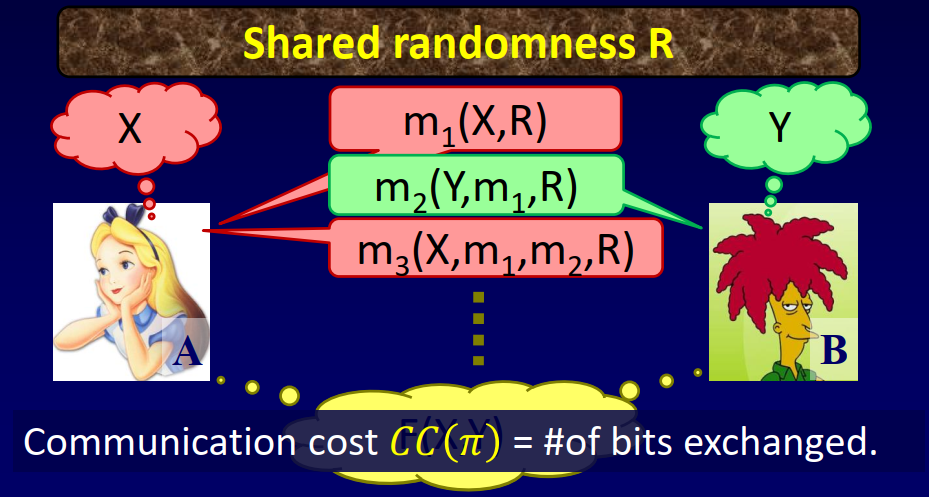

In the two-party communication complexity setting, two players (Alice and Bob) are given inputs $X$ and $Y$. They are also allowed to use a randomness source $R$. A protocol $\pi$ is just a formalization of a conversation: each message in $\pi$ is allowed to depend on the speaker’s input, on the conversation so far, and on the public randomness. The communication cost of a protocol is the number of bits communicated during its execution. The communication complexity $CC(T)$ of a task $T$ is the smallest communication cost of a protocol $\pi$ solving $T$. In the context of communication complexity, $T$ is typically the task of “computing a given function $F(X,Y)$ with error probability $<\varepsilon$”.

An instructive example is the Equality problem. Alice is given an $n$-bit string $X$, Bob is given an $n$-bit string $Y$, and they would like to determine whether $X=Y$. It can be shown that this can be accomplished with error $<\varepsilon$ using $k \sim \log (1/\varepsilon)$ bits of communication. Alice will compute a random hash $h(X)$ of lenght $k$ on her input $X$ and send the value to Bob. Bob will compare $h(X)$ to $h(Y)$, and will return ’equal’ if they match. There is a $2^{-k}$ probability of hash collision, which means that ’equal’ is returned with probability $\approx 2^{-k}$ even when $X\neq Y$. Interestingly, a zero-error protocol for equality requires $n+1$ bits of communication.

Another function with many applications in lower bounds is Disjointness. Alice and Bob are given subsets $X,Y\subset \lbrace 1,\ldots,n\rbrace$ (wich can be represented as length-$n$ bit-strings), and need to determine whether they have an element in common. $Disj_n(X,Y)=1$ if the sets are disjoint, and $0$ if they intersect.

The direct sum problem (in any model of computation) asks whether it costs $k$ times as much to perform $k$ independent copies of a task $T$ as it costs to perform one copy, or whether one gets a “volume discount”. When direct sum holds, one gets a powerful lower bounds tool — a lower bound $L$ on $T$ gets amplified into a lower bound of $k\cdot L$ on the task $T^k$ of performing $k$ copies of $T$. When direct sum fails, new interesting algorithms follow. A famous example of such a failure is matrix-vector multiplication. A counting argument shows that one needs $>n^2$ operations to mutiply an $n\times n$ matrix $A$ by a vector $v$. At the same time, multiplying $A$ by $n$ different vectors $v_1,\ldots,v_n$ is just the problem of multiplying two $n\times n$ matrices, which can be done faster than $n\cdot n^2=n^3$ via fast matrix multiplication.

The Direct Sum Problem for randomized communication complexity asked whether the direct sum property holds for randomized communication complexity. That is, whether $CC(T^k)\gtrsim k\cdot CC(T)$? It turns out that trying to answer this question is closely related to understanding the information complexity of $F$.

Information complexity is defined similarly to communication complexity, with information cost replacing communication cost. The (two-party) information cost of a protocol $\Pi$ on inputs $(X,Y)$ is defined to be the amount of information the participants learn about each other’s inputs during the execution of the protocol. Fortunately, the information-theoretic notation makes this quantity easy to formalize: $$ IC(\Pi):= I(X;\Pi|Y) + I(Y;\Pi|X). $$ The first term corresponds to what Bob (who knows $Y$) learns about Alice’s input ($X$) from the protocol $\Pi$. The second term corresponds to what Alice learns. The information complexity of a task $T$ over inputs $(X,Y)$ is defined as the smallest possible information cost of a protocol solving $T$. $$ IC(T):= \inf_{\text{$\Pi$ solves $T$}} IC(\Pi). $$ The infimum here is necessary, since it is possible that there is a sequence of successful protocols $\Pi_1,\Pi_2,\ldots$ that get ever longer while revealing an ever smaller amount of information (in fact, this happens for the simple task of computing the two-bit AND function).

It turns out that the amortized (per-copy) communication complexity of a task $T$ is equal to its information complexity, at least when a vanishing amount of error is allowed. Let $T(X,Y)$ be a task that allows for a small amount of error $\ve=o(1)$. Let $CC(T^k)$ be the communication complexity of $k$ copies of $T$, and let $IC(T)$ be its information complexity. Then information is equal to amortized communication:

Theorem [BR'11]: $\displaystyle{\lim_{k\rightarrow\infty} \frac{CC(T^k)}{k} = IC(T)}$.

This theorem gives an immediate blueprint for proving direct sum theorems for (randomized) communication complexity. To show (for example) that $CC(T^k) \gtrsim k\cdot CC(T)$, one can show that $IC(T)\gtrsim CC(T)$. This inequality, more commonly written as $CC(T)\lesssim IC(T)$ is known as the interactive compression question. It asks whether a protocol $\pi$ that solves $T$ while revealing little information can be “compressed” into a protocol $\pi’$ that uses little communication.

In the context of one-way communication near-perfect compression is generally possibly. For example Huffman coding allows one to encode a message with entropy $H(M)$ using at most $H(M)+1$ bits in expectation. It is generally the case that a protocol with $r$ rounds of communication can be compressed into $O(IC(\Pi)+r)$ bits of communication. Unfortunately, the protocol achieving $IC(T)$ may have an unbounded number of rounds, making such a compression useless in the general interactive setting.

It turns out that it is possible to compress a general protocol $\pi$ whose information cost is $I$ and whose communication cost is $C$ into a protocol $\pi’$ whose communication cost is $\tilde{O}(\sqrt{I\cdot C})$. This leads to a partial direct sum theorem for randomized communication:

Theorem [BBCR'10]: $\displaystyle{CC(T^k)}=\tilde{\Omega}(\sqrt{k}\cdot CC(T))$.

At the same time, Ganor, Kol, and Raz showed a separation between information and communication complexity:

Theorem [GKR'15]: There is a family of functions whose information complexity is $n$ and whose communication complexity is $2^{\Omega(n)}$.

Moreover, it can be shown that this separation is tight - communication complexity is always at most exponential in information complexity. The GKR'15 theorem rules out a tight direct sum theorem for communication complexity. It still remains open whether the $\sqrt{k}$ in BBCR'10 can be improved, e.g. to $k^{1-\varepsilon}$.

In light of the BR'11 and GKR'15 results, information complexity becomes the “correct” measure for studying amortized cost of two-player randomized communication complexity. The connection from BR'11 between information and amortized communication can be further deepened by a direct product theorem. A direct sum theorem gives a lower bound on the amount of resources required to accomplish $k$ copies of a task. A direct product theorem further says that trying to solve $k$ copies of the task with fewere resources will fail except with an exponentially small probability.

Theorem [BRWY'13,BW'14]: If $I$ bits of information are required to compute a single copy of a function $f(x,y)$ under an input distribution $\mu$, then any communication protocol that attempts to solve $k$ copies of $f$ with input distributed according to $\mu^k$ using $o(k\cdot I)$ bits of communication will fail except with an exponentially small probabiliy $2^{-\Omega(k)}$.

At the heart of the proof of the direct product theorem is applying information-theoretic formalism which treats the “success event” as just another piece of information. Formalism such as the chain rule allows to make statements of the form “succeeding on the first copy does not reveal too much about inputs to the second copy” formal.

Previously, such reasoning has been used successfully to prove the parallel repetition theorem for two-prover games. Two-prover games warrant a separate discussion, but it should be mentioned that formalism from the direct product theorem from communication complexity can be lifted to re-prove the parallel repetition theorem, and give the only known proof of the parallel repetition theorem in the low-success-probability regime [BG'15].

Turning from abstract complexity-theoretic results to concrete ones, let us consider the information complexity of specific functions. The simplest functions are ones are of the form $f:\lbrace 0,1\rbrace\times\lbrace 0,1\rbrace \rightarrow \lbrace 0,1\rbrace$, where Alice and Bob are each given a single bit of input. Of those, only the AND function (and equivalent transformations) is interesting from the information complexity perspective. Other functions are either constant, amount to one-way data transmission (projection functions), or to a two-way data-exchange (the XOR function).

Generally speaking, we do not know an efficient procedure for computing the information complexity of a function from its truth table. In fact, even proving that information complexity is computable appears to be non-trivial [BS'16]. Fortunately, in the case of the two-bit AND, it is possible to describe the information-theoretically optimal protocol.

Generally speaking, the optimal protocol depends not only on the function $f$ being computed but also on the prior distribution $\mu$ of inputs - this is because the amount of information revealed by a protocol $\pi$ depends on the prior distribution $\mu$.

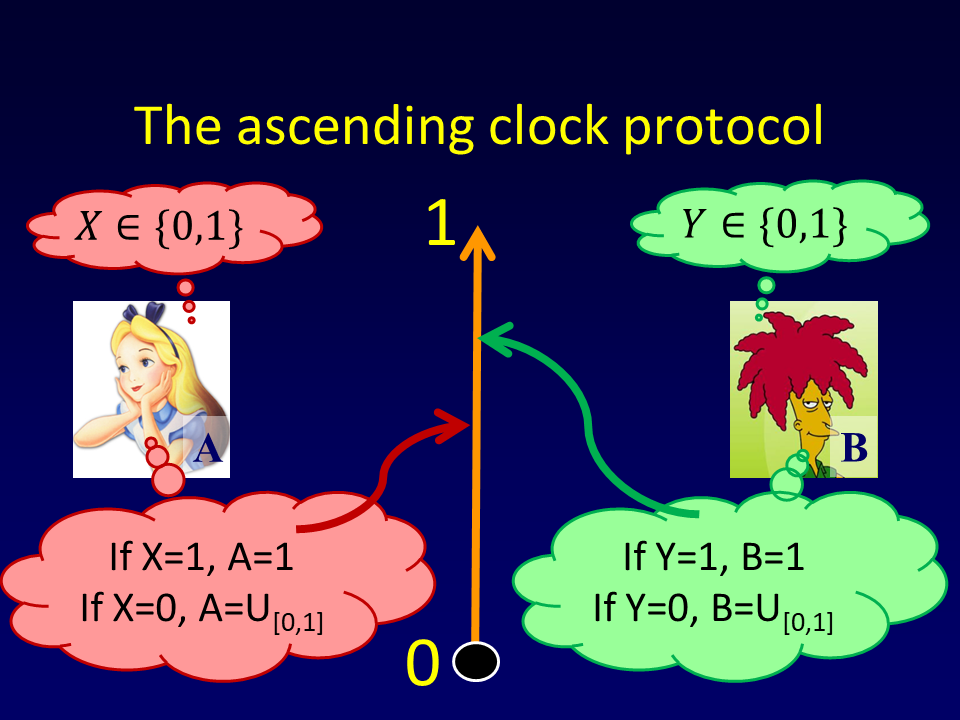

The ascending clock protocol [BGPW'13]:

- If $x=1$, Alice sets $A:=1$, otherwise picks a uniformly random $A\in_U [0,1]$;

- If $y=1$, Bob sets $B:=1$, otherwise picks a uniformly random $B\in_U [0,1]$;

- A continuous clock counts time $t$ from $0$ to $1$;

- If $A$ is reached, Alice raises her hand and the protocol terminates;

- If $B$ is reached, Bob raises his hand and the protocol terminates;

- If the protocol terminates at time $t<1$ output $AND(x,y)=0$;

- If the protocol terminates at time $t=1$ output $AND(x,y)=1$.

Based on the optimality of the ascending clock protocol, one can get exact bounds on several two-party communication problems that are based on $n$ copies of the two-bit AND function:

- Intersection. The randomized communication complexity of finding the intersection of two subsets of $\lbrace 1,\ldots,n\rbrace$ (which amounts to $n$ copies of AND) is $C_\wedge \cdot n \pm o(n)$, where $C_\wedge\approx 1.4923$ is a constant obtained by maximizing an explicit function.

Interestingly, when no error is allowed, the constant increases to $\log_2 3\approx 1.585$ [AC'94].

Disjointness. The randomized communication complexity of deciding whether two subsets of $\lbrace 1,\ldots,n\rbrace$ intersect (which amounts to $n$ copies of AND where the prior $\mu$ puts zero weight on $(1,1)$) is $C_{DISJ} \cdot n \pm o(n)$, where $C_{DISJ}\approx 0.4827$.

Small set Disjointness The randomized communication complexity of deciding whether two subsets of $\lbrace 1,\ldots,n\rbrace$ of size $k$ intersect (which amounts to $n$ copies of AND where the prior $\mu$ puts zero weight on $(1,1)$ and $\frac{k}{n}$ weight on the $(0,1)$ and $(1,0$ entries) is $\frac{2}{\ln 2} \cdot k \pm o(k)$.

In this case, even the fact that the communication complexity is $O(k)$ and not $O(k \log k)$ is somewhat surprising [HW'07].

As discussed earlier, the strength of information-theoretic formalism is its ability to formalize vague statements about states of “knowledge” into precise (and correct) mathematical statements. Within complexity theory there are many examples of this from the last two decades. Let us highlight an easy-to-state recent example, motivated by streaming algorithms.

An algorithm is given access to a sequence $x_1,\ldots,x_n$ of uniformly random bits. At the end, it needs to guess whether there were more $0$’s in the sequence or more $1$’s. The algorithm only needs to be correct on $51%$ of the inputs. This means that it is ok to only ouput $1$ on sequences with more than $\frac{n}{2}+\sqrt{n}$ $1$’s, output $0$ on sequences with more than $\frac{n}{2}+\sqrt{n}$ $0$’s, and give a random answer otherwise. The constrained resource is the amount of memory $S$ the algorithm can store while reading the stream.

One obvious solution is to maintain a register that at time $t$ stores $R_t=\sum_{j=1}^t x_t$, and outputing $1$ if $R_n>n/2$. This solution requires memory $S=\log n + O(1)$. Can one do substantially better? It turns out that the answer is tight:

Theorem [BGW'20] Solving the approximate majority problem requires memory $S\ge \Omega(\log n)$.

Note that even though the theorem’s statement appears “obviously true”, it is more delicate than one would expect: (1) it is possible to distinguish sequences with $\frac{n}{2}+n^{0.67}$ $1$’s from uniform sequences using only $O(\log \log n)$ memory; (2) it is possible to solve the problem using $O(\log n)$ memory while only storing $O(1)$ information about the $x_j$’s seen so far. The relevant quantity which must be at least $\Omega(\log n)$ for a typical $t$ turns out to be:

$$ \sum_{j=1}^t I(R_t; X_j | R_{j-1}). $$

Once this quantity is correctly identified, the proof follows relatively standard proof patterns.

It is very interesting to consider the kinds of problems where information-theoretic reasoning has not been successful so far. It is natural to try the same approach for more than two parties. In a three-party setting one can define the information complexity of problems based on the amount of information the participants need to reveal to each other in order to solve the problem. It is not difficult to prove a direct sum theorem showing that the (3-party) information complexity of $k$ copies of a task $T$ are $k$ times the information complexity of a single copy. Unfortunately, such a statement turns out to be vacuous! Communication amoung 3 or more “honest-but-curious” parties supports information-theoretically secure multi-party computation, which means that any function can be computed by 3 or more parties without revealing anything to each other (except for the answer in the end). Thus the “direct sum” theorem in this case turns out to be of the form “$k\times 0 = 0$”.

This pattern appears to repeat itself in any computational model that is rich enough to support information-theoretically secure computation. For example, consider communication over a channel where Alice and Bob each submit a bit $x_i$ and $y_i$, and learn the value $x_i\wedge y_i$ of the AND of the two bits. Information-theoretic lower bounds over such a channel would have had interesting complexity-theoretic implications. Once again, one can redo information complexity over such a channel and obtain direct sum results. Once again, the result is vacuous, since such a channel is powerful enough to be able to implement information-theoretically secure two party computation [K'91]. The same is true in the context of Arthur-Merlin games [GPW'16].

Understanding whether this is a surmountable technical barrier, or a true conceptual one (that requires new tools or even new conjectures) is a topic which I hope to work on in the future.

- A 15 minutes high level overview on theoretical computer science and information complexity: [pdf]

- A survey can be found here.

- Quantum information complexity is a very interesting topic not covered above. Some pointers can be found here and here.

- The papers section on this page.