Misc projects

Let $A$ be an $n\times n$ matrix. It gives rise to the quadratic form $$\sum_{i,j} A_{ij} x_i y_j.$$ The Grothendieck constant $k$ bounds the ratio between the maximum of this form when $x_i,y_j$ are unit vectors in a Hilbert space and the maximum of this form when $x_i,y_j\in {-1,1}$ are just real numbers. In other words, $k$ is the smallest number such that for all $A$,

$$\left|\max_{||X_i||,||Y_j||\leq 1} A_{ij} \langle X_i, Y_j \rangle\right| \leq k\cdot \left|\max_{x_i,y_j\in {-1,1}} A_{ij} x_i y_j\right|.$$

Algorithmically, the Grothendieck constant can be viewed as the integrality gap between what can be attained by a general (vector) solution and the integral solution to the optimization problem of maximizing $\sum_{i,j} A_{ij} x_i y_j$. A natural strategy for giving an upper bound on $k$ is to come up with a (possibly randomized) rounding scheme that converts vectors $X_i, Y_j$ into numbers $x_i,y_j$ while losing a factor of at most $k$ in the objective function.

Rounding vectors to numbers has had many important applications in algorithms. For example, the Goemans-Williamson MAX CUT approximation algorithm represents the MAXCUT instance as a (tractable) optimization problem over vectors, and then uses a random projection onto a line to obtain an approximate integral solution. The approximation ratio is exactly the worst-case ratio between the value attained by the vector solution versus the integral solution.

In 1977, Krivine proposed a natural rounding scheme for the Grothendieck inequality, proving an upper bound $k\le c_k= \frac{\pi}{2\ln (1+\sqrt{2})}\approx 1.7822$, which he conjectured to be tight. The scheme (similarly to the rounding schemes in the algorithms from decades to follow), involved transforming the vectors and then applying a random projection of the vectors to a line (with vectors projected to the positive side assigned a $+1$, and those to the negative side a $-1$). In 2011 we disproved Krivine’s conjecture that $k=c_k$ by showing that $k<c_k$.

This is done by devising a better rounding scheme (or, rather showing that one exists via a delicate perturbation argument). In the process, we show that, most likely, a two-dimensional rounding strategy can beat the one dimensional strategy of projecting vectors onto a line. The two-dimensional strategy would partition the plane into two regions $R_{+1}$ and $R_{-1}$, and map vectors to numbers by projecting them to the plane and then assigning them to $\pm 1$ based on the region into which they fall. The one-dimensional strategy corresponds to $R_{+1}$ and $R_{-1}$ each being a half-plane.

The diagram on the right gives an educated guess on what the partition of the plane $\mathbb R^2$ might look like for the optimal two-dimensional Krivine scheme. If Krivine’s conjecture were true, the optimal partition would have been just a half-plane.

Reference: Mark Braverman, Konstantin Makarychev, Yury Makarychev, Assaf Naor. The Grothendieck constant is strictly smaller than Krivine’s bound, 2011.

Links: paper on arXiv; FOCS'11 version from IEEE; open access version from Forum of Mathematics, Pi.

Consider an environment with a finite set of alternatives $A_1,\ldots,A_k$ and agents who have quasi-linear preferences. That is, each agent $i$ has utility $u_{ij}$ for alternative $A_j$, and if she has to pay an amount $p_i$ her utility becomes $u_{ij}-p_i$. A direct mechanism consists of an allocation rule $f$ and payment rule $p$. The allocation rule maps each profile of valuations to a probability vector over the set of possible alternatives. For example, the second price auction on one item amounts to the allocation rule being “the highest bidder gets the item”, and the payment collected from the winner equals the second-highest bid (and no payment collected from other players).

An allocation rule $f$ is said to be implementable if there exists a payment rule $p$ so it is safe for each agent to report his true valuation to the mechanism $(f,p)$") regardless of the reports of all other agents. In other words, the payment rule $p$ makes truthful reporting a dominant strategy for all players. Understanding which allocation rules are implementable is a fundamental concern in mechanism design. Myerson has shown in his seminal 1981 paper, that when the set of alternatives is single dimensional (for example when a single item is auctioned for sale), an allocation rule is implementable if an only if it is monotone in the valuation of a player. Informally, monotonicity means that higher demand for an outcome by a player will result in a greater-or-equal allocation of that outcome.

For multidimensional settings, such as selling multiple goods, Rochet has shown in 1987 that a stronger condition, called cycle-monotonicity, of an allocation rule is a necessary and sufficient condition for implementing it. Cyclic monotonicity however is a considerably more difficult condition to work with than monotonicity. Monotonicity is a condition on every pair of values, whereas cyclic monotonicity is a condition on every finite sequence of values. This gives rise to the natural question of when does monotonicity imply cycle-monotonicity (and thus implementability).

Saks and Yu (2005) have shown that when the domain of (multidimensional) valuations is convex, monotonicity is necessary and sufficient for implementing an allocation rule. We show that convexity is also necessary in the following sense: if the domain of valuation is not convex, there always exists an allocation rule that is monotone yet not implementable. In other words, when the domain of possible valuations is not convex, local constraints alone are not sufficient to guarantee implementability.

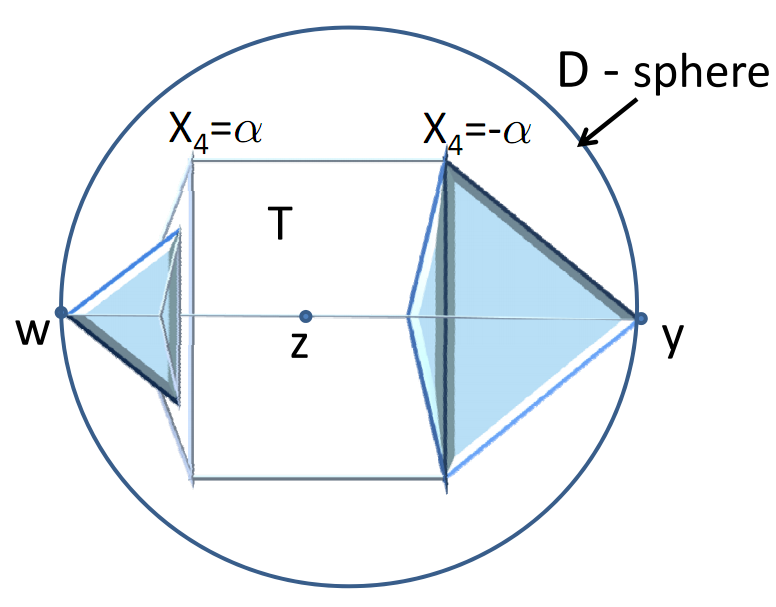

For each non-convex domain, the proof involves the construction of an allocation rule that is not implementable. The figure on the left shows a component of the proof for dimensions 3 and higher.

Reference: Itai Ashalgi, Mark Braverman, Avinatan Hassidim, Dov Monderer. Monotonicity and Implementability, Econometrica, 78(5), 2010.

Links: Econometrica 78(5), 2010; [pdf] [Supplementary material]